"Nobody's Going to Notice": Theo Triantafyllidis on Institutional Barriers

I first met Theo Triantafyllidis just after he'd finished his time at UCLA's Digital Media Arts program. How to Everything (2016), one of his early works of real-time simulation that use game environments as open-ended labratories of spontaneous acitvity.

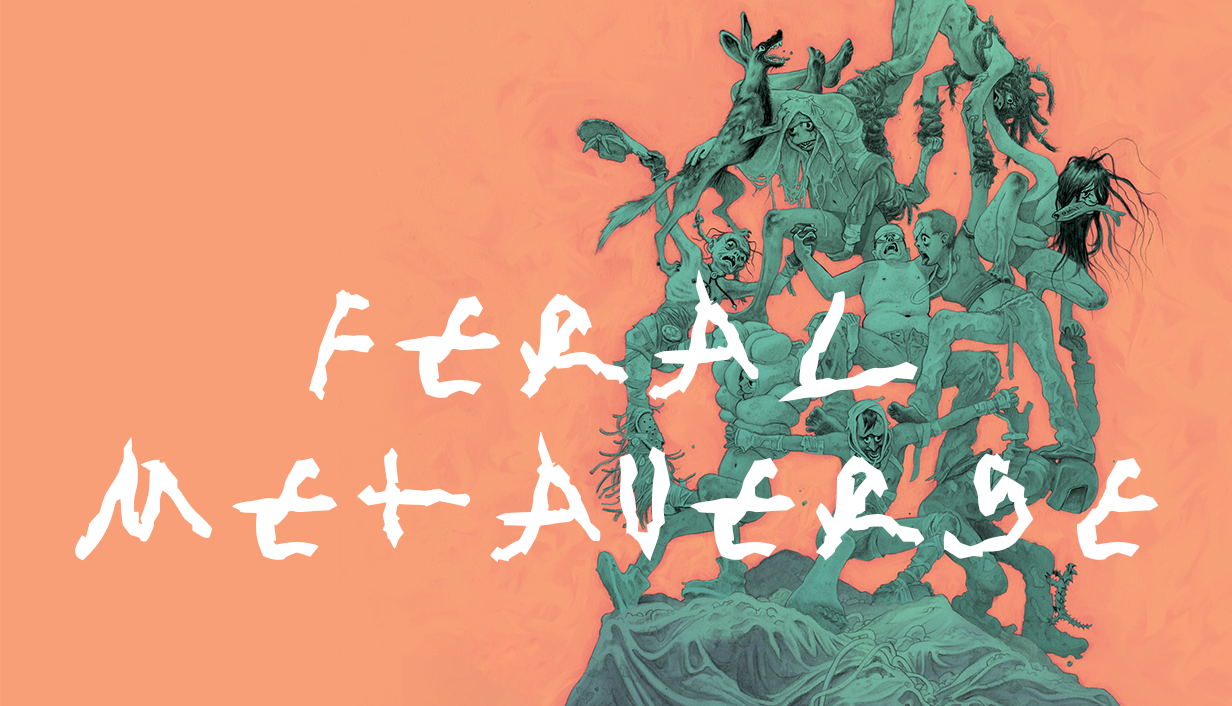

Since then, Triantafyllidis has exhibited at major institutions, including the Whitney Museum, Centre Pompidou, and was part of the Venice Biennale's Hyper Pavilion. His work ranges from Pastoral, an intimate anti-game about a muscular orc running through an infinite hayfield, to Feral Metaverse, an ambitious eight-player multiplayer game with a custom medieval catapult rig that's been in development for over three years. We worked together to soft-launch the game last spring.

In this conversation, we go deep on the practical realities of exhibiting interactive work: Why IT staff aren't the same as technical infrastructure. How institutions fund physical installations but not digital development, or vice versa. Why a game that takes two weeks to build might tour internationally while a three-year project struggles to find the right venue. And what it means when audiences bring their player psychology into the gallery space—that instinct to test boundaries and break systems that makes games fundamentally different from other art forms.

Hope you enjoy this conversation (or you can listen to it on podcast as well!)

What Museums Miss About Exhibiting Game-Based Art: Technical Infrastructure and Development Realities

Jamin Warren: For artists working with game-based arts, has collaborating with galleries and museums become easier as your career has progressed, or has it become more complicated?

Theo Triantafyllidis: The art world operates as a trust-based system. Breaking in feels very hard initially, but once you establish curatorial credibility, it helps tremendously. I've been extremely lucky—over the past ten years, I've seen a significant shift in how the art world perceives video games as art and artists making games. Key institutional exhibitions have definitely opened doors for continuing presentations.

JW: Even with that progress, what do institutions still not understand about what your work needs?

TT: The development cycles for game projects—the time, resources, and effort required to complete ambitious work. Game industry standards and gamer expectations are extremely high right now because of overall production quality. That creates a tough situation.

I also keep running into funding challenges. My projects have both digital components—the video game itself—and physical sculptural installations. With traditional art pipelines, there's usually funding for physical installation but not necessarily for digital development. Or it's reversed—funding exists for digital production, but physical production falls under a different department and slips through the cracks. Accessing both funding pools simultaneously gets tricky.

JW: Are there particular institutions handling this well?

TT: I've had great experiences working with Onassis ONX in New York. They've developed a solid program for showcasing this work. The Serpentine and Hans Ulrich Obrist's program has built substantial infrastructure over the past few years—research, development, and a real ecosystem supporting long-term development and ambitious installations.

JW: How do you communicate what makes games meaningful without defaulting to spectacle? The art world responds well to big visual statements, but games communicate meaning through personal interaction—that intimate relationship between player and controller.

TT: That's a continuous issue in game criticism generally. People talking about games often prefer to discuss themes or narrative elements rather than the overall game experience. Novel interaction methods or interesting mechanics are much less discussed—both in the art world and in games criticism. It's harder to put those experiences into words.

"I also keep running into funding challenges."

JW: What do you wish museums understood before accepting your work? Let's start with appropriate timelines for production, testing, and iteration.

TT: Timeline is definitely an important challenge. Artists, including myself, often get this completely wrong—scoping a game correctly, understanding how much can be done in what time with what resources. But that's quite practical.

The bigger issue is understanding the impact of games culture generally—how it's become a central driving force in culture and criticism. A big section of the art world is completely oblivious to that shift. Finding the language to analyze this work, understanding it as its own medium rather than bringing analytical tools from other media—that would be very useful.

Why IT Staff Don't Equal Technical Infrastructure for Interactive Work

JW: What's the difference between having IT staff versus having appropriate infrastructure to showcase your work?

TT: Art institutions often don't have the proper position in their crews to manage these installations. When an institution takes on a larger video game show, the challenges aren't completely understood. An IT person or someone who usually installs video art might not have the same skill set needed to maintain a video game during an exhibition.

Making sure a game can flawlessly run and essentially fix itself during eight-hour daily runs, unsupervised, with audiences constantly coming in and trying to break it—it has to be foolproof and self-sufficient, or it needs someone occasionally checking that everything works. That's also a challenge.

JW: People bring their personal player psychologies into the gallery space. They want to test boundaries. How should institutions budget for ongoing maintenance versus just installation?

TT: Testing boundaries is expected behavior. Most gamers, myself included, first try to understand a game's boundaries, its rules, how easy they are to break, how they're enforced, and what player agency is. Gamers constantly want that negotiation with games, and they bring it to exhibition spaces.

For maintenance during exhibition runs, having an invigilator or an IT person occasionally check helps. Even completely outside the game's scope, there's the operating system constantly fighting for its own rights in the background, plus other software usually installed on computers running games. It's a live system someone has to take care of.

" Testing boundaries is expected behavior."

Development Timelines: From Two-Week Prototypes to Multi-Year Projects

JW: Let's break down two specific works. Starting with Pastoral (2019)—what did that installation require?

TT: That's funny because Pastoral took the least time to develop. It was an offshoot from another project I made during downtime. After having an orc character as my avatar for a long time, I wanted to free this character and let them have a chill moment.

The whole game is a very muscular androgynous orc running in a hayfield—an anti-game in the sense that it feels like a scene from a longer video game where you're running from one quest to the next, but you have a small moment of downtime where nothing is happening. You can enjoy the view of the game world. You have anticipation of the next thing coming, but I wanted to expand this moment to infinity—create this infinite hayfield where you can run around and look at the sunset without anything bothering you.

This proved very well suited for the exhibition format. It's the work I've exhibited most and keep getting invitations for because it plays well with an ambient feeling. The game doesn't ask too much—no tutorial, no complex controls or mechanics to learn. It gives an aesthetic moment to appreciate in an exhibition space, letting audiences freely go in and out, spending as much time as they want.

With Feral Metaverse, which is much more complex and designed for longer online play, there's constant struggle around complexity—how complex should controls and interactions be while keeping it intuitive enough that someone can understand what to do even spending just 20 seconds on it in an exhibition?

Pastoral (2019)

JW: For Feral Metaverse with its custom medieval catapult rig and eight-player installation—what was the collaboration structure with venues? Starting with Nagel Draxler gallery, then moving to the Group Hug exhibition at Whitney?

TT: Nagel Draxler was extremely generous, providing exhibition space for a first prototype before the game even existed, without much to show when we started conversations. From the beginning, I knew this was an ambitious, complicated project that might take a really long time to finish. But I wanted to integrate audience feedback and make the development process more transparent for the general public.

I saw that the Berlin exhibition was a place to show a first MVP—a minimum viable prototype. I worked very DIY with a small budget, almost like a game jam with a few friends handling music, concept art, and 3D characters. Without really knowing the multiplayer networking side or having done it before, I pushed myself to try to make the simplest functional prototype that communicated the game's core ideas.

It was fun showing it at that stage. I think audiences appreciated this openness—that this was a prototype in development, which you don't often see in exhibitions. I also got very useful feedback for continuing development.

What Institutions Should Know Before Commissioning Game-Based Work

JW: It sounds like part of the approach should involve figuring out exactly where work is in the artist's life cycle. Setting realistic expectations for what can be done is super helpful. It's okay, particularly for smaller institutions, not to feel like they need to pull off something huge. They can be the first step in a work that's going to grow, not complete in any shape or fashion, just providing a venue at its nascent stage.

For both Pastoral and Feral Metaverse, do you have minimum viable technical setups versus ideal scenarios?

TT: For Pastoral, it's pretty easy. For all game works, I'm super cautious about not having crazy gaming computer requirements. I spend a lot of time optimizing to make work run on relatively normal PCs. That helps with exhibitions because if you tell an institution you want them to buy or rent a $3,000 gaming PC, it changes the conversation quite a bit compared to a PC they might have around or used for a game shown a couple of years ago.

For Feral Metaverse, I haven't quite figured this out yet, as I've only shown it tied to custom sculptural rigs I make for it—either four or eight players. I've been invited to venues or festivals without a budget to ship the whole sculpture, which makes sense. But I also didn't want to show the work in a regular seated desktop environment. The game is playable by at least two people and is quite fun for two players. I'm trying to figure out the best artistic solution for maintaining the installation idea while making it super easy to install.

Building Curatorial Literacy for Interactive Art Practice

JW: What forms of structural support make a difference beyond more money?

TT: Having moved my studio to Greece, finding and building a good game development team has been an issue. Some institutions that are more ongoing parts of the discourse around games and art have already built small communities of specialized people around them. That's also a very valuable resource.

"I knew this was an ambitious, complicated project that might take a really long time to finish. But I wanted to integrate audience feedback and make the development process more transparent for the general public."

JW: Looking forward, what should museums or institutions be doing now to be credible with game-based art?

TT: The HR part is quite important. Maybe hiring—thinking more long-run and hiring people who can create infrastructure to facilitate this kind of work long-term is interesting. Getting onboard a curator more well-versed in this language, or a tech person who can install this type of work—that's a good investment.

But institutions showing video games can also easily fall into the trap of being too hyped about trying this new medium and repeating hurtful clichés about the medium, or exhibiting it as a novelty thing rather than trying to place it within general arts discourse. Treating it as a medium within the context of everything else—not thinking "let's do a video game show," but more casually integrating games in regular curation—is actually more important, maybe.

JW: I completely agree. Doing video game shows where the through line is just that they are video game projects—that's not a sufficient curatorial point of view. Ideally, games are part of a body of work, just one expression of whatever the main curatorial theme might be.

Having basic games literacy helps a lot. If you're interested, spend time playing commercial video games. That's obviously a touchpoint for artists making this work, but it helps build sensitivities for what you're looking to exhibit. It's like wanting to show video art but never having watched a movie, or last watching one as a kid—your efforts are going to be hamstrung because you haven't spent time with the medium.

TT: That also helps the artist and curatorial conversation push both sides into interesting territory. Artists sometimes feel hopeless—like "I can spend the next six months developing this new mechanic for the game, but nobody's going to notice. If I just have a simple first-person controller, everyone's going to say 'yeah, this is a video game artwork.'" Making sure there's proper curatorial feedback can really help both sides.

JW: Any opportunities you see that museums and institutions are missing?

TT: Art institutions have cultural capital and prestige toward the general public. This situation helps the medium of video games be taken more seriously generally, and helps people playing video games not be shy or weird about it. Overall, it can create a much healthier medium and community. It's a very good opportunity.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.